After many additional experiments using special apparatus of lenses and mirrors which he built, he laid down his new ideas about light and vision in his seven volumes Book of Optics.

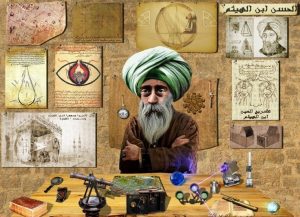

The dramatic story of Ibn al-Haytham’s life

The story of Ibn al-Haytham’s life and discoveries is truly extraordinary. Born in the year 965 in Basra, he made significant contributions to our understanding of both vision and light, bringing important new insights into both of these subjects. His brilliant breakthrough, however, came at a time of the darkest episode of his life.

Ibn al-Haytham grew up at a time when schools and libraries flourished in the Muslim civilization. Students had access to highly trained scholars who could teach a variety of subjects, including law, literature, medicine, mathematics, geography, history and art. Debates and discourses were popular and took place in Arabic. Scholars enjoyed discussing ideas from newly translated ancient manuscripts.

Ibn al-Haytham’s scholarly reputation spread well beyond Basra.

He is known to have said, “If I would be given the chance, I would implement a solution to regulate the Nile flooding”. This claim reached al-Hakim, the Fatimid caliph in Egypt who invited him to Cairo. Confident of his own abilities, Ibn al-Haytham boasted that he would tame the great Nile River by building a dam and reservoir. But when he saw the extent of the challenge and the marvelous remains of ancient Egypt on the river banks, he reconsidered his own boast thinking. If such a huge project could be done, he reasoned, it would have been done by the brilliant builders of the past who had left us such fantastic architectural relics. He returned to Cairo to inform the caliph that his solution was not possible.

Knowing that that particular caliph did not entertain failure and that his life would be at risk if he were to disappoint him, Ibn al-Haytham feigned madness to avoid the caliphs’ wrath. He knew that Islamic law would protect a mad person from bearing responsibility for his failure. Despite the caliph’s wild swings of mood, he nevertheless abided by Islamic law. Rather than executing or expelling Ibn al-Haytham from Cairo, the caliph decided to put the scholar under permanent protective custody. That was required by law in order to ensure his safety and that of others. Ibn al-Haytham was placed under what amounted to house arrest, far from the lively discourses and debates to which he was accustomed.

Yet it just as life was at its bleakest moment. Ibn al-Haytham might have made the dazzling discovery for which he is best remembered. Legend says, one day he saw light shining through a tiny pinhole into his darkened room – projecting an image of the world outside onto the opposite wall. Ibn al-Haytham realized that he was seeing images of objects outside that were lit by the Sun. From repeated experiments he concluded that light rays travel in straight lines, and that vision is accomplished when these rays pass into our eyes.

Ibn al-Haytham confirmed his discovery by experimenting with his dark room (calling it Albait Almuzlim)- translated into Latin as camera obscura, which simply means “dark room”.

After many additional experiments using special apparatus of lenses and mirrors which he built, he laid down his new ideas about light and vision in his seven volumes Book of Optics. He was released from prison on the death (disappearance) of the caliph.

Ibn al-Haytham died at the age of 74 in 1040. His greatest work, the Book of Optics, had perhaps begun from the confines of imprisonment and was completed around the year 1027- but its impact rippled out across the whole world. Both his optical discoveries, and the fact that they had been validated using hands-on experiments, would influence those who came after him for centuries.

So how did that influence shine its light on later generations? In the early 12th century, Toledo in Spain was the focus of a huge effort to translate Arabic books into Latin. Christian, Jewish and Muslim scholars flocked to the city, where they lived alongside one another and worked together to translate the old knowledge into Latin and then into other European languages. Ibn al-Haytham’s Book of Optics as well as some of his other scientific works were translated into Latin making them available to European scientists including Roger Bacon, Johannes Kepler and even Leonardo da Vinci.

How Ibn al-Haytham changed the course of science

Ibn al-Haytham’s discoveries in optics and vision overturned centuries of misunderstanding. In his experiments, he observed that light coming through a tiny hole travelled in straight lines and projected an image onto the opposite wall.

But he realized that light entering the eye was only the first step in seeing. He built on the work of Greek physician Galen who had provided a detailed description of the eye and the optic pathways. Today the oldest-known drawing of the nervous system is from Ibn al-Haytham’s Book of Optics, in which the eyes and optic nerves are illustrated. [IYL2015 Call to action]

Ibn al-Haytham suggested that only the light rays that hit the surface of the eye head-on would pass into the eye, creating a representation of the world. It was Kepler in the sixteenth century who corrected this and proposed that the object of sight – what is seen comes from both perpendicular and angular rays that hit the eye to form an inverted image on the retina. [IYL2015 Call to action]

Among Ibn al-Haytham’s other insights was his understanding of the crucial role of visual contrast. For example, he realized the color of an object depends on the color of the surroundings, and that a contrast of brightness levels explains why we can’t see the stars during daytime.

Ibn al-Haytham also subscribed to a method of empirical analysis to accompany theoretical postulates that is similar in certain ways to the scientific method we know today. He realized that the senses were prone to error, and he devised methods of verification, testing and experimentation to uncover the truth of the natural phenomena he perceived. Up until this time, the study of physical phenomena had been an abstract activity with occasional experiments.

In search of evidence, Ibn al-Haytham studied lenses, experimented with different mirrors: flat, spherical, parabolic, cylindrical, concave and convex. His practical results were clear:

“Visual objects seen by us through light refraction – across thick material such as water and glass – are bigger than their real size”, he wrote.

After his death, Ibn al-Haytham’s writings were more influential in Latin than Arabic. The only significant work in Arabic that built on Ibn al-Haytham’s ideas was produced in the early part of the fourteenth century (in present day Iran) by Kamal al-Din al-Farisi, who was himself a brilliant scientific thinker.

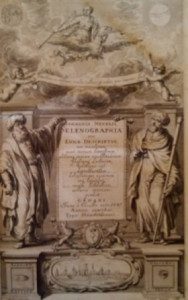

Polish astronomer Johannes Hevelius honoured Ibn al-Haytham’s contribution to optics. This illustration is from Hevelius’ s famous Selenographia. Hevelius puts Ibn al-Haytham as the equal of Galileo in this illustration from his book the first to chart the Moon’s surface as seen through a telescope.

When Ibn al-Haytham’s Book of Optics was translated into Latin, it had great influence and was widely studied/read. It was published as a print edition in 1572 so that it could be made more easily available. The Polish astronomer Johannes Hevelius chose to honor Ibn al-Haytham, alongside Galileo, in his most famous work on the Moon, Selenographia, published in 1647.

Some questions Ibn al-Haytham raised remained unsolved for a thousand years. One such was called ‘Alhazen’s problem’ for which he offered a geometrical solution: “Given a light source and a spherical mirror, find the point on the mirror where the light will be reflected to the eye of an observer”. Ibn al-Haytham solved this problem geometrically but it remained unsolved using algebraic methods until it was finally solved in 1997 by the Oxford mathematician Peter M Neumann.

And yet, some mysteries remain. Ibn al-Haytham affirmed that an optical illusion was the reason for the Moon appearing so big when it’s low in the sky close to the horizon in comparison to its size when at the zenith- and still no one knows why this happens. This, and other questions in science, has yet to be solved – leaving a legacy of intrigue for us to tackle today.

———–

Taken with slight editorial modifications from www.ibnalhaytham.com.

Arabic

Arabic English

English Spanish

Spanish Russian

Russian Romanian

Romanian korean

korean Japanese

Japanese