The Arabic Language

Introduction

It is this intimate connection between the Qur’an and Arabic which gave the language its special status and contributed to the Arabization of diverse populations.

Arabic is one of the world’s major languages with over 300 million people in various Arab countries who use it as a mother tongue.(1) It is also used extensively as the major language in a non-Arab country, the Central African Republic of Chad, and as a minority language in several other countries, including Afghanistan, Israel (where both Arabic and Hebrew are official languages), Iran, and Nigeria. In 1974, Arabic was adopted as one of the six United Nations official languages, joining Chinese, English, French, Russian and Spanish. Over one billion Muslims in places like India, Indonesia, Pakistan and Tanzania study Arabic as a foreign or second language for liturgical and scholarly use. In the United States, several Muslim and Arab communities employ Arabic in their daily interactions and for religious purposes.

History and Development of Arabic

Arabic belongs to the Afro-Asiatic (or Hamito-Semitic) family of languages that consists of over three hundred languages, some of which are extinct and some used marginally as liturgical languages. Arabic and Hebrew are the two prime examples of living Semitic languages while Hausa and various dialects of Berber are examples of surviving Hamitic languages.

The earliest known example of Arabic is an inscription found in the Syrian Desert dating back to the fourth century A.D. The pre-Islamic Arab tribes who lived in the Arabian Peninsula and neighboring regions had a thriving oral poetic tradition. But it was not systematically collected and recorded in written form until the eighth century A.D. This poetic language, probably the result of the fusion of various dialects, came to be regarded as a literary or elevated style which represented a cultural bond among different tribes.

Prophet Muhammad received his messages from God in Arabic through the Angel Gabriel over a period of twenty-three years, 610-632 A.D. The Holy Qur’an, containing these messages, was originally committed to memory by professional reciters (hufaz and qura’). With the spread of Islam, different accents for the pronunciation of the Qur’an came into use until a standardized version (with notations for different accents) was completed under the third Caliph, Uthman Ibn ‘Affan, in the mid-seventh century A.D. As more and more non-Arabic speakers were drawn to Islam, the Qur’an became the most important bond among Muslims, Arabs and non-Arabs alike, revered for its content and admired for the beauty of its language. Arabs, regardless of their religion, and Muslims, regardless of their ethnic origin, hold the Arabic language in the highest esteem and value it as the medium of a rich cultural heritage. It is this intimate connection between the Qur’an and Arabic which gave the language its special status and contributed to the Arabization of diverse populations.

The Spread of Arabic

By the beginning of the eighth century, the Islamic Arab Empire had spread from Persia to Spain, resulting in the interaction between Arabs and local populations who spoke different languages. In Syria, Lebanon, and Palestine, where the majority of the population spoke some dialect of Aramaic and where Arab tribes had been present in the vicinity, the local languages were for the most part replaced by Arabic. In Iraq, Arabic became the dominant language among a population who spoke Aramaic and Persian. A more gradual process of Arabization occurred in Egypt where Coptic and Greek were the two dominant languages. In North Africa, where Berber dialects were spoken and still are used in some parts, the process of Arabization was less complete. Persia and Spain, however, retained their respective languages.

In the early days of the Empire, the majority of the population would not have been Arabic monolinguals. The interaction of Arabic with other languages led to the borrowing of new vocabulary which enriched the language in areas such as government, administration, and science. This, in addition to the rich internal resources of Arabic, enabled the language to become a suitable medium for governing a vast empire.

Under the Umayyad dynasty (661-750 A.D.), with Damascus as the center of power, Arabic continued its tradition of excellence as the language of poetry, enriched its literature with translations from Persian and other languages, and acquired new terminology in various fields of study which included linguistics, philosophy, and theology. Under the Abbasid rule from Baghdad (750-1258 A.D.), Arabic literature reached its golden age as linguistic studies reached a new level of sophistication. Many scholars, Arabs and non-Arabs, Muslims, Christians and Jews, participated in the development of intellectual life using Arabic as their preferred language. A systematic effort at translation from various sources had made Arabic the most suitable scholarly medium of the day in disciplines such as philosophy, mathematics, medicine, geography and various branches of science. Many of the words readily borrowed during this period were easily assimilated into Arabic and later transmitted to other languages.

A period of decline began in the eleventh century as the result of several factors including the start of the Crusades, the political unrest in Spain, Mongol and Turkish invasions from the East, and internal divisions within the Empire. This marked a period of relative stagnation for Arabic although its status as the language of Islam was never threatened.

A period of decline began in the eleventh century as the result of several factors including the start of the Crusades, the political unrest in Spain, Mongol and Turkish invasions from the East, and internal divisions within the Empire. This marked a period of relative stagnation for Arabic although its status as the language of Islam was never threatened.

The nineteenth century saw a period of intellectual revival which began in Egypt and Syria and spread to the rest of the Arab world, beginning with the Napoleonic expedition to Egypt in 1798. The expedition provided for the introduction of the first Arabic printing press to Egypt and the translation of numerous Western literary works into Arabic. This initial contact was continued by Muhammad Ali, an enlightened Egyptian ruler, who sent students to France and other countries to study various disciplines; they returned to Egypt as teachers and writers. Lebanon had been in contact with the West as early as the seventeenth century, maintaining a strong religious connection with some European groups. Other Western influences came from Arab immigrants to the Americas and from missionaries who contributed to the establishment of foreign languages, mainly English and French, as important components of the educational system in parts of the Arab world.

The initial enthusiastic thrust towards westernization clashed with nationalistic independence movements that were a natural response to European colonialism in the region. These movements were usually linked to the two major pillars of Arab nationalism: the Muslim religion and the Arabic language. Thus, Arab intellectuals found themselves torn between the rich and glorious heritage of the past and a future which became increasingly associated with Western technology and modernity. The nineteenth century saw the beginning of the development of Arabic as a viable modern language.

Elements of Arabic Structure

Arabic, like all Semitic languages, is characterized by the use of certain morphological patterns (patterns of word formation) to derive words from abstract roots that represent general semantic notions or meanings. These roots usually consist of three consonants which form the basis for the formation of numerous words from any given root. For instance, the root KTB, which is associated with the notion of ‘writing,’ is found in the verb stems KaTaB ‘wrote’ and KTuB ‘write’ which can be conjugated by the addition of appropriate prefixes and suffixes. To illustrate further how word stems can be derived from various roots, it is helpful to look at the makeup of a root in terms of the position that each consonant (C) occupies relative to the two other consonants. Thus the stem KaTaB can be represented by the pattern C1aC2aC3where C1=K, C2=T, and C3=B. A modification of the stem to C1aC2C2aC3(doubling the medial consonant of the root) results in the derivation of the stem KaTTaB which has the causative meaning ‘made (someone) write.’ On the other hand, lengthening the first vowel of the stem (C1aaC2aC3) derives KaaTaB, meaning ‘corresponded.’ The addition of the prefix ta- results in taKaaTaB, with the reciprocal meaning ‘exchanged letters (with someone).’ There are fifteen possible patterns that a verb root can theoretically have, although five of these are extremely rare. Each of these patterns can be modified to indicate a passive voice and an imperfect present) tense: e.g. KuTiB ‘was written,’ yaKTuB ‘writes,’ yuKTaB ‘is written.’

By modifying the root consonants, using various vowel combinations, and utilizing different prefixes and suffixes, several possibilities exist for deriving nouns, adjectives and adverbs from any given root. The following words, for example, all of which are derived from KTB, can be found in a typical dictionary: KiTaaB ‘book,’ KuTuBii ‘bookseller,’ KuTTaaB‘elementary or Qur’anic school,’ KuTayyiB ‘booklet,’ KiTaaBa ‘writing, script,’ KiTaaBaat ‘writings, essays,’ KiTaaBii ‘written, literary,’ maKTaB‘ office, bureau,’ maKTaBii ‘of an office,’ maKTaBa ‘library,’ miKTaaB‘typewriter,’ muKaaTaBa ‘correspondence,’ iKtiTaaB ‘enrollment, registration,’ istiKTaaB ‘dictation,’ KaaTiB ‘writer,’ maKTuuB ‘letter,’ muKaaTiB ‘correspondent,’ and muKtaTiB ‘subscriber’ (Cowan). Many of these words can be pluralized, e.g. KuTuB ‘books,’ KuTTaB ‘writers,’ maKTaBaat ‘libraries,’ and some can occur with a feminine ending, e.g.KaaTiBa ‘female writer,’ muKaaTiBa ‘female correspondent,’ andKaaTiBaat ‘female writers.’ The preceding examples illustrate a rich and versatile morphological pattern of word derivation that can theoretically allow for hundreds of Arabic words to be derived from a single root.

Orthography

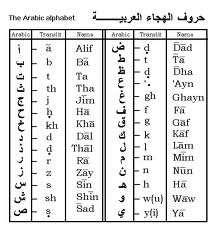

The Arabic writing system is an adaptation of the Nabatean script which evolved from Aramaic writing system. It consists of twenty-eight letters representing consonant sounds and is written from right to left. Three of these letters representing the consonants /’, w, y/ are also used for representing the long vowel sounds /aa, uu, ii/, respectively.(2) The short vowel sounds /a, u, i/, which may be represented with diacritic marks above or below a letter, are normally omitted except in situations where semantic ambiguity or serious errors in pronunciation cannot be tolerated. The Qur’an and the Arabic Bible are always printed with a full representation of short vowel sounds and also with other diacritics which signify the doubling of consonants or the absence of any vowel sounds following a particular consonant.

The Arabic writing system is an adaptation of the Nabatean script which evolved from Aramaic writing system. It consists of twenty-eight letters representing consonant sounds and is written from right to left. Three of these letters representing the consonants /’, w, y/ are also used for representing the long vowel sounds /aa, uu, ii/, respectively.(2) The short vowel sounds /a, u, i/, which may be represented with diacritic marks above or below a letter, are normally omitted except in situations where semantic ambiguity or serious errors in pronunciation cannot be tolerated. The Qur’an and the Arabic Bible are always printed with a full representation of short vowel sounds and also with other diacritics which signify the doubling of consonants or the absence of any vowel sounds following a particular consonant.

Arabic script is cursive, meaning that certain letters must be connected to others whether in writing or printing. While no distinction exists between capital and lower case letters, a letter may occur in more than one form (as illustrated in the Arabic Alphabet table) depending on its position in the word and what other letters surround it.

To illustrate the system, it may be helpful to use some examples of words derived from the root KTB ‘writing,’ which is represented in Arabic by the letters ,ب,ت,ك respectively. When these letters are connected to each other from right to left, they result in a word which is spelled كتب. The absence of any long vowels in this word means that all the possible vowels which can occur in this word are short. Hence the word can be ambiguously read as KaTaBa ‘(he) wrote,’ KuTiBa ‘was written,’ KaTTaBa ‘made (someone) write,’ or KuTuB ‘books.’ Which of the above readings is the appropriate one is determined by the context. The word KaaTiB ‘writer’ and KiTaaB ‘book,’ both with long vowel sounds are written as كاتب and كتاب , respectively.

In pre-Islamic times, Arabic script suffered from a number of deficiencies including the lack of letters for certain consonant sounds and the absence of any system for indicating vowel sounds. The present system is the result of some major reforms which were introduced when the script was found inadequate as a tool for recording and preserving the Holy Qur’an. This close association with the Qur’an bestowed a sanctified status on a script that arose from a humble beginning. This enabled it to develop into a unique art form not equaled by any other calligraphic tradition.

With the spread of Islam, many non-Arabs found themselves learning Arabic in order to be able to read the Qur’an. Thus many languages which came under the influence of Arabic through Islam adopted the use of the Arabic script. These languages, most of which were non-Semitic in origin, included Farsi (Persian), Pashto, Kashmiri, Urdu, Sindhi, Malay, and others (Kaye).

Dialectal Varieties

Several regional dialects of Arabic exist, some of which may not be readily intelligible to speakers from other regions. To varying extents, these language varieties show differences in grammar, pronunciation, and vocabulary. Arabic speakers refer to these spoken varieties as ‘aammiyya, or colloquial, as opposed to the literary or classical fusha language which is acquired through formal instruction. This linguistic duality, commonly referred to as diglossia in the linguistic literature, involves the complementary use of two varieties (high and low) in specific contexts.

The high variety is Classical Arabic; the ultimate example of which is the language of the Qur’an, is used in formal situations. The low variety refers to various regional vernaculars or colloquial varieties used for everyday interactions. While this often-cited distinction between Classical and Colloquial Arabic may be useful, it merely represents two poles of a continuum which more accurately characterizes a complex linguistic situation. Two other varieties are Modern Standard Arabic and Educated Spoken Arabic. Modern Standard Arabic, a continuation of Classical Arabic with some modifications in grammar and an extensive addition of modern vocabulary, is the language of written communication throughout the Arabic-speaking world. When educated speakers from different dialectal backgrounds communicate orally, they tend to use what is sometimes known as Educated Spoken Arabic — a mixture of colloquial speech and Modern Standard Arabic.

Notes:

1. The League of Arab States consists of twenty-two members: Algeria, Bahrain, Comoros, Djibouti, Egypt, Iraq, Jordan, Kuwait, Lebanon, Libya, Mauritania, Morocco, Oman, Palestine, Qatar, Saudi Arabia, Somalia, Sudan, Syria, Tunisia, United Arab Emirates, and Yemen. In some of these countries Arabic may share its official status with some other language (French in Djibouti and Somali in Somalia) or it may not be the first language of a large segment of the population (the Kurdish community in Iraq, the Berbers in North Africa, and various ethnic groups in Southern Sudan).

2. The symbol /’/ represents a consonant sound which is known ashamza in Arabic and as a “glottal stop” in phonetics. The closest English equivalent for this sound is the pronunciation of tt in the words ‘bottle’ and “button” in some dialects of American English.

To be continued…

Works Cited:

– Abu-Absi, Samir. “The Modernization of Arabic: Problems and Prospects,” Anthropological Linguistics, Fall 1986, 337-348.

– Cannon, Garland. The Arabic Contributions to the English Language: An Historical Dictionary. Alan S. Kaye, Collaborator. Wiesbaden: Otto Harrassowitz, 1994.

– Cowan, J. Milton, ed. Arabic-English Dictionary: The Hans Wehr Dictionary of Modern Written Arabic, 4th ed. Ithaca, New York: Spoken Language Services, Inc., 1994, 951-52.

– Alan S. Kaye, “Adaptations of Arabic Script,” in Peter T. Daniels and William Bright, eds. The World’s Writing Systems. New York and Oxford: Oxford University Press, 1996 743-62.

—————

Courtesy http://historyofislam.com with slight editorial modifications.

Dr. Samir Abu-Absi, Professor Emeritus of English at the University of Toledo, received his B.A. degree in English from the American University of Beirut and his M.A. and Ph.D. in Linguistics from Indiana University. His teaching and scholarly interests have focused on the study of language structure — particularly English and Arabic, the application of linguistic principles to language instruction, and the relationship between language and culture.

Arabic

Arabic English

English Spanish

Spanish Russian

Russian Romanian

Romanian korean

korean Japanese

Japanese