By John Noble

Spain’s Islamic centuries (AD 711-1492) left a particularly rich heritage of exotic and beautiful palaces, mosques, minarets and fortresses in Andalusia, which was always the heartland of Al-Andalus (as the Muslim- ruled areas of the Iberian Peninsula were known). These buildings make Andalusia visually unique in Europe and have to be classed as its greatest architectural glory. Nor is the legacy of the Islamic era just a matter of the big, eye-catching monuments: after the Christian re-conquest of Andalucia (1227-1492), many Islamic buildings were simply repurposed for Christian ends. As a result, many of today’s Andalucian churches are simply converted mosques (most famously at Cordoba), many church towers began life as minarets, and the zigzagging streets of many an old town – Granada’s Albayzin district is just one famous example originated in labyrinthine Islamic-era street plans.

Spain’s Islamic centuries (AD 711-1492) left a particularly rich heritage of exotic and beautiful palaces, mosques, minarets and fortresses in Andalusia, which was always the heartland of Al-Andalus (as the Muslim- ruled areas of the Iberian Peninsula were known). These buildings make Andalusia visually unique in Europe and have to be classed as its greatest architectural glory. Nor is the legacy of the Islamic era just a matter of the big, eye-catching monuments: after the Christian re-conquest of Andalucia (1227-1492), many Islamic buildings were simply repurposed for Christian ends. As a result, many of today’s Andalucian churches are simply converted mosques (most famously at Cordoba), many church towers began life as minarets, and the zigzagging streets of many an old town – Granada’s Albayzin district is just one famous example originated in labyrinthine Islamic-era street plans.

The Omayyads

Islam – the word means ‘Surrender’ or ‘Acceptance’ (to the will of Allah) – was founded by the prophet Mohammed in the Arabian city of Makkah in the 7th Century AD. It spread rapidly to the north, east and west, reaching Spain in 711. In 750 the Damascus- based Omayyad dynasty of caliphs, rulers of the Muslim world, were overthrown by the revolutionary Abbasids, who shifted the caliphate to Baghdad. Just one of the Omayyad family, Abu’l-Mutarrif Abd ar-Rahman bin Muawiya, escaped. Aged only 20, he made for Morocco and thence Spain. In 756 he managed to set himself up as an independent emir, Abd ar-Rahman I, in Cordoba, launching a dynasty based in that city that lasted until 1009 and made Al-Andalus, at the western extremity of the Islamic world, the last outpost of Omayyad culture.

The Horseshoe Arch: Omayyad architecture in Spain was enriched by styles and techniques taken up from the Christian Visigoths, whom the Omayyads replaced as rulers of the Iberian Peninsula. Chief among these was what became almost the hallmark of Spanish Islamic architecture – the horseshoe arch – so called because it narrows at the bottom like a horseshoe, rather than being a simple semicircle.

The Horseshoe Arch: Omayyad architecture in Spain was enriched by styles and techniques taken up from the Christian Visigoths, whom the Omayyads replaced as rulers of the Iberian Peninsula. Chief among these was what became almost the hallmark of Spanish Islamic architecture – the horseshoe arch – so called because it narrows at the bottom like a horseshoe, rather than being a simple semicircle.

The Mezquita of Cordoba

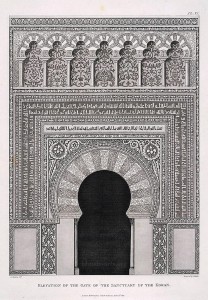

The oldest significant surviving Spanish Islamic building is also arguably the most magnificent and the most influential. The great Mezquita of Cordoba was founded by Abd ar-Rahman I in AD 785 and underwent major extensions under his successors Abd ar-Rahman II in the first half of the 9th Century, Al-Hakim II in the 960s and Al-Mansur in the 970s.

Abd ar-Rahman I’s initial mosque was a Square split into two rectangular halves: a covered prayer hall, and an open ablutions courtyard where the faithful would wash before entering the prayer hall. The Mezquita’s prayer hall broke away from the verticality of earlier great Islamic buildings such as the Great Mosque of Damascus and the Dome of the Rock in Jerusalem. Instead it created a broad horizontal space recalling the yards of desert homes that formed the original Islamic prayer spaces, and conjured up visions of palm groves with mesmerizing lines of two-tier, red-and-white-striped arches in the prayer hall. The prayer hall maintained a reminder of the ‘basilical’ plan of some early Islamic buildings in having a central ‘nave’ of arches, broader than the others, leading to the mihrab, the niche indicating the direction of Makkah (and thus of prayer) that is key to the layout of any mosque.

In its final 10th-century form the Cordoba Mezquita’s roof was supported by 1293 columns.

The Mezquita’s later enlargements extended the lines of arches to cover an area of nearly 120 sq meters, making it one of the biggest of all mosques. These arcades afford ever-changing perspectives, vistas disappearing into infinity and plays of light and rhythm that rank among the Mezquita’s most mesmerizing and unique features. The most important enlargement was carried out in the 960s by Al-Hakim II, who created a magnificent new mihrab, decorated with superb Byzantine mosaics imitating those of the Great Mosque of Damascus, one of the outstanding 8th-century Syrian Omayyad buildings. In front of the mihrab Al-Hakim II added a new royal prayer enclosure, the maksura. The maksura’s multiple interwoven arches and lavishly decorated domes were much more intricate and technically advanced than anything previously seen in Europe. The maksura formed part of a second axis to the building, an aisle running along in front of the wall containing the mihrab known as the qibla wall because it indicates the qibla, the direction of Makkah. This transverse axis, at right angles to the central nave, creates the T-plan that features strongly in many mosques.

Al-Hakim’s Mezquita is the high point of the splendid l0th-century ‘caliphal’ phase of Spanish Islamic architecture – so called because this was the era of the Cordoban caliphate founded by Al-Hakim’s father, Abdar-Rahman III. The plan of Al-Hakim II’s building is obscured by the Christian cathedral that was plonked right in the middle of the mosque in the 16th Century, but when you are in the Mezquita it is still quite possible to work out the dimensions of each phase of its construction.

Islamic Decorative Motifs: The mosaic decoration around Al-Hakim II’s 10th-century mihrab portal exhibits all three of the decorative types permissible in Islamic holy places: stylized inscriptions in classical Arabic, geometric patterns, and stylized plant and floral patterns. At this early stage of Hispano-Islamic art, the plant and floral decorations were still relatively naturalistic: later they become more stylized, more geometrical and more repetitive, adopting the mathematically conceived patterns known as arabesques. By the time Granada’s Alhambra was built in the 14th Century, vegetal and geometric decorative forms had become almost indistinguishable.

Other Omayyad Buildings

In AD 936 Abd ar-Rahman III built himself a new capital just west of Cordoba. Medina Azahara, named after his favorite wife, Az-Zahra, was planned as a royal residence, palace and seat of government, set away from the hubbub of the city in the same manner as the Abbasid royal city of Samarra, north of Baghdad. Its chief architect was Abd ar-Rahman III’s son, Al-Hakim II, who later embellished the Cordoba Mezquita so superbly. In contrast to Middle Eastern palaces, whose typical reception hall was a domed iwan (hall opening to a forecourt), Medina Azahara’s reception halls had a ‘basilical’ plan, each with three or more parallel naves – similar to mosque architecture.

Though Medina Azahara was wrecked during the collapse of the Cordoba caliphate less than a Century after it was built, it has now been partly reconstructed. From its imposing horseshoe arches, exquisite stucco work and extensive gardens, it’s easy to see that it was a large and lavish place.

Relatively few other buildings survive from the Omayyad era in Spain, but the little 1Oth-century mezquita in remote Almonaster la Real is one of the loveliest Islamic buildings in the country. Though later converted into a church, the mosque remains more or less intact. It’s like a miniature Version of the Cordoba Mezquita, with rows of arches forming five naves, the central one leading to a semi- circular mihrab.

Eleventh Century Palaces

Most of the ‘petty kings’ of the turbulent taifa (small kingdoms) period lived in palaces of some kind, but only a few of these remain. The Alcazaba at Malaga, though rebuilt later, still has a group of 11th century rooms with a caliphate-style row of horseshoe arches. Within Almeria’s Alcazaba is the Palacio de Almotacin, constructed by the city’s strongest taifa ruler.

Most of the ‘petty kings’ of the turbulent taifa (small kingdoms) period lived in palaces of some kind, but only a few of these remain. The Alcazaba at Malaga, though rebuilt later, still has a group of 11th century rooms with a caliphate-style row of horseshoe arches. Within Almeria’s Alcazaba is the Palacio de Almotacin, constructed by the city’s strongest taifa ruler.

House and Palaces of Andalusia by Patricia Espinosa De Los Monteros and Francesco Ventura is a coffee-table tome full of beautiful photography that just might inspire some design ideas for your own palace.

The Almoravids & Almohads

The rule of the Berber Almoravids from Morocco, from the late 11th to mid-12th centuries, yielded few notable buildings in Spain, but the second wave of Moroccan Berbers to conquer Al-Andalus, the Almohads, constructed huge Friday mosques in the main cities of their empire, among them Seville. The design of the mosques was simple and purist, with large prayer halls conforming to the T-plan of the Cordoba Mezquita, but the Almohads introduced some important and beautiful decorative innovations. The bays where the naves meet the qibla wall were surmounted by cupolas or stucco muqarnas (stalactite or honeycomb vaulting composed of hundreds or thousands of tiny cells or niches). On walls, large brick panels with designs of interwoven lozenges were created.

From the late 12th Century, tall, square, richly decorated minarets started to appear. The Giralda, the minaret of the Seville mosque, is the masterpiece of surviving Almohad buildings in Spain, with its beautiful brick panels. The Seville mosque’s prayer hall was demolished in the 15th Century to make way for the city’s cathedral, but its ablutions courtyard, Patio de los Naranjos, and its northern gate, the handsome Puerta del Perdön, survive.

Another Almohad mosque, more palace-chapel than large congregational affair, stands inside the Alcäzar at Jerez de la Frontera. This tall, austere brick building is based on an unusual octagonal plan inscribed within a Square.

Many rooms and patios in Seville’s Alcäzar palace-fortress date from Almohad times, but only the Patio del Yeso, with its superbly delicate trelliswork of multiple interlocking arches, still has substantial Almohad remains.

Muqarnas (honeycomb or stalactite vaulting) originated in Syria or Iran: the Almoravid mosque at Tlemcen, Morocco, was the first western Islamic building to feature it.

The Nasrids

The Nasrid emirate of Granada, named after its founder, Mohammed ibn Yusuf ibn Nasr, was the last Muslim redoubt on the Iberian Peninsula, enduring for two and a half centuries (1249-1492) after all the rest of Spain had been taken by the Christians. The Nasrid rulers lavished most of their art-and-architecture budget on one single palace complex of their very own – but what a palace complex it is.

The Alhambra

Granada’s magnificent palace-fortress, the Alhambra, is the only surviving large medieval Islamic palace complex in the world. It’s a palace-city in the tradition of Medina Azahara but is also a fortress, with 2km of walls, 23 towers and a fort-within-a-fort, the Alcazaba. Within the Alhambra’s walls were seven separate palaces, mosques, garrisons, houses, offices, baths, a summer residence (the Generalife) and exquisite gardens.

The Alhambra’s designers were supremely gifted landscape architects, integrating nature and buildings through the use of pools, running water, meticulously clipped trees and bushes, windows framing vistas, carefully placed lookout points, interplay between light and dark, and contrasts between heat and cool. The juxtaposition of fountains, pools and gardens with domed reception halls reached a degree of perfection suggestive of the paradise described in the Qur’an. In keeping with the Alhambra’s partial role as a sybarite’s delight, many of its defensive towers also functioned as miniature summer palaces.

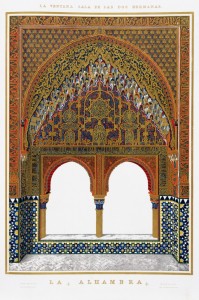

A huge variety of densely ornamented arches adorns the Alhambra. The Nasrid architects refined existing decorative techniques to new peaks of delicacy, elegance and harmony. Their media included sculptured stucco, marble panels, carved and inlaid wood, epigraphy (with endlessly repeated inscriptions of ‘There is no conqueror but Allah’) and colorful tiles. Plaited star patterns in tile mosaic have since covered walls the length and breadth of the Islamic world, and Nasrid Granada is the dominant artistic influence in the Maghreb (Northwest Africa) even today.

The marquetry ceiling of the Alhambra’s Salon de Comares employs more than 8000 tiny wooden panels.

Granada’s splendor reached its peak under emirs Yusuf I (r 1333-54) and Mohammed V (r 1354-59 and 1362-91). Each was responsible for one of the Alhambra’s two main palaces. Yusuf created the Palacio de Comares (Comares Palace). The brilliant marquetry ceiling of the Salön de Comares (Comares Hall) here, representing the seven levels of the Islamic heavens and capped by a cupola representing the throne of Allah, served as the model for Islamic-style ceilings in State rooms for centuries afterwards. Mohammed V takes credit for the Palacio de los Leones (Palace of the Lions), focused on the famed Patio de los Leones (Patio of the Lions), with its colonnaded gallery and pavilions and a central fountain channeling water through the mouths of 12 stone lions. This palace’s Sala de Dos Hermanas (Hall of Two Sisters) features a fantastic muqarnas dorne of 5000 tiny cells, recalling the constellations.

Mudejar & Mozarabic Architecture

The label Mudejar – from Arabic mudayan (domesticated) – was given to Muslims who stayed on in areas re-conquered by the Christians, who often employed the talents of gifted Muslim artisans. Mudejar buildings are effectively part of Spain’s Islamic heritage. You’ll find Mudejar or part-Mudejar churches and monasteries all over Andalucia (Mudejar is often found side by side with the Christian Gothic style), but the classic Mudejar building is the exotic Palacio de Don Pedro, built in the 14th Century inside the Alcäzar of Seville for the Christian King Pedro I of Castile. Pedro’s friend Mohammed V, the Muslim emir of Granada, sent many of his best artisans to work on Pedro’s palace, and as a result the Palacio de Don Pedro is effectively a Nasrid building, and one of the best of its kind – especially the beautiful Patio de las Doncellas at its heart, with a sunken garden surrounded by exquisite arches, tiling and plasterwork.

One hallmark of Mudejar style is geometric decorative designs in brick or stucco, often further embellished with tiles. Elaborately carved timber ceilings are also a mark of the Mudejar hand. Artesonado is the word used to describe ceilings with interlaced beams leaving regular spaces for decorative insertions. True Mudejar artesonados generally bear floral or simple geometric patterns.

The term Mozarabic, from musta`rib (Arabized), refers to Christians who lived, or had lived, in Muslim-controlled territories in the Iberian Peninsula. Mozarabic architecture was, unsurprisingly, much influenced by Islamic styles. It includes, for instance, the horseshoe arch. The majority of Mozarabic architecture is found in northern Spain: the only significant remaining Mozarabic structure in Andalucia – but well worth seeking out for its picturesque setting and poignant history – is the rockcut church at Bobastro.

Islamic Fortifications

With its bordersconstantly underthreat and its subjects often rebellious, it’s hardly surprising that Al- Andalus boasts more Islamic Castles and forts than any comparably sized territory in the World.

Caliphate Era

The 10th Century saw heaps of forts built in Al-Andalus’ border regions, and many fortified garrisons constructed in the interior. Designs were fairly simple, with low, rectangular towers and no outer rings of walls. Two of the finest caliphate-era forts are the oval one at Banos de la Encina in Jaen province and the hilltop Alcazaba dominating Almeria.

Taifa Period

In this 11th-century era of internal strife, many towns bolstered their defenses. A fine example is Niebla in Huelva province, which was enclosed by walls with massive round and rectangular towers. So was the Albayzin area of Granada. Niebla’s gates show a new sophistication, with barbicans (double towers defending the gates) and bends in their passageways to impede attackers.

Almohad Fortifications

In the 12th and early 13th centuries the Almohads rebuilt many city defenses, such as those at Cordoba, Seville and Jerez de la Frontera. Cordoba’s Torre de la Calahorra and Seville’s Torre del Oro are both well-constructed bridgehead towers from this era.

Nasrid Fortifications

Many defensive fortifications as at Antequera and Ronda, and Mälaga’s Castillo de Gibralfaro were restored as the Granada emirate strove to survive in the 13th, 14th and 15th centuries. Big rectangular corner towers such as those at Malaga and Antequera suggest the influence of the Christian enemy. The most spectacular fort of the era – though better known as a palace – is Granada’s Alhambra.

—————–

Source: islamic-arts.org

John Noble, originally from England’s Ribble Valley, and his wife, Susan Forsyth, decided to try life in an Andalusian mountain village for a year or so in the mid-1990s. They are still there, along with their now bilingual, multicultural children Isabella and Jack. A writer with a specialism in Spain and Latin America, John has travelled throughout Andalusia and loves its history and architecture.

Arabic

Arabic English

English Spanish

Spanish Russian

Russian Romanian

Romanian korean

korean Japanese

Japanese