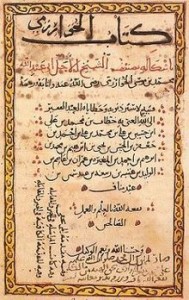

Muhammad Ibn Musa Al-Khowarizmi, the father of algebra, was a mathematician and astronomer. He was summoned to Baghdad by Al-Mamun and appointed court astronomer. From the title of his work, Hisab Al-Jabr wal Mugabalah (Book of Calculations, Restoration and Reduction), Algebra (Al-Jabr) derived its name.

Muhammad Ibn Musa Al-Khowarizmi, the father of algebra, was a mathematician and astronomer. He was summoned to Baghdad by Al-Mamun and appointed court astronomer. From the title of his work, Hisab Al-Jabr wal Mugabalah (Book of Calculations, Restoration and Reduction), Algebra (Al-Jabr) derived its name.

His book On the Calculation with Hindu Numerals, written about 825, was principally responsible for the diffusion of the Indian system of numeration (Arabic numerals) in the Islamic lands and the West.

Al-Khowarizmi left his name to the history of mathematics in the form of Algorism (the old name for arithmetic).

Al-Khowarizmi emphasized that he wrote his algebra book to serve the practical needs of the people concerning matters of inheritance, legacies, partition, lawsuits and commerce.

In the twelfth century Gerard of Cremona and Roberts of Chester translated the algebra of Al-Khowarizmi into Latin. Mathematicians used it all over the world until the sixteenth century.

Traditional systems had used different letters of the alphabet to represent numbers or cumbersome Roman numerals, and the new system was far superior, for it allowed people to multiply and divide easily and check their work. The merchant Leonardo Fibonacci of Pisa, who had learned about Arabic numerals in Tunis, wrote a treatise rejecting the abacus in favor of the Arab method of reckoning, and as a result, the system of Hindu-Arabic numeration caught on quickly in Central Italy. By the fourteenth century, Italian merchants and bankers had abandoned the abacus and were doing their calculations using pen and paper, in much the same way we do today.

In addition to his treatise on numerals, al-Khwarizmi also wrote a revolutionary book on resolving quadratic equations. These were given either as geometric demonstrations or as numerical proofs in an entirely new mode of expression. The book was soon translated into Latin, and the word in its title, al-Jabr, or transposition, gave the entire process its name in European languages, algebra, understood today as the generalization of arithmetic in which symbols, usually letters of the alphabet such as A, B, and C, represent numbers. Al-Khwarizmi had used the Arabic word for “thing” (shay’) to refer to the quantity sought, the unknown. When al-Khwarizmi’s work was translated in Spain, the Arabic word shay’ was transcribed as xay, since the letter x was pronounced as sh in Spain. In time this word was abbreviated as x, the universal algebraic symbol for the unknown.

Robert of Chester’s translation of al-Khwarzmi’s treatise on algebra opens with the words dixit Algorithmi, “Algorithmi says.” In time, the mathematician’s epithet of his Central Asian origin, al-Khwarizmi, came in the West to denote first the new process of reckoning with Hindu-Arabic numerals, algorithmus, and then the entire step-by-step process of solving mathematical problems, algorithm.

The Muslims of the 9th Century, including Abu Al-Wafaa’ turned Algebra into science. They created the zero and the decimal point.

Abu Al-Wafaa’ was the first person to demonstrate the sine theorem for spherical triangle: sin (a+b) = sin a cos b – cos a sin b. The word ‘sine’ is the exact translation of the Arabic word Jayb.

——————

Taken with slight editorial modifications from islamic-study.org, with the same title which reads, Muslims’ Contribution in Algebra.

Arabic

Arabic English

English Spanish

Spanish Russian

Russian Romanian

Romanian korean

korean Japanese

Japanese