Originally posted 2019-02-19 00:10:24.

African dignitaries and educational experts, at a December 6-10 conference in Johannesburg, South Africa, are discussing ways of reforming Africa’s dismal educational systems. The conference highlight thus far was a stirring address by South African President Thabo Mbeki, in which he called for educational reform as the basis of a 21st-century African renaissance. Mbeki’s speech provided a much-needed emphasis on the importance of education as the means for African renewal. But given the current indolence of Western education on which Mbeki and others seem to be basing their vision of reform, the conference must not forget to reassert traditional forms of education as a means of coping in the 21st century.

African dignitaries and educational experts, at a December 6-10 conference in Johannesburg, South Africa, are discussing ways of reforming Africa’s dismal educational systems. The conference highlight thus far was a stirring address by South African President Thabo Mbeki, in which he called for educational reform as the basis of a 21st-century African renaissance. Mbeki’s speech provided a much-needed emphasis on the importance of education as the means for African renewal. But given the current indolence of Western education on which Mbeki and others seem to be basing their vision of reform, the conference must not forget to reassert traditional forms of education as a means of coping in the 21st century.

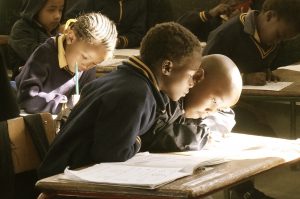

While the impoverished continent of Africa suffers at all levels of society, the often-appalling circumstances in which African children find themselves are well documented. Estimates quoted by the BBC on August 5 reveal that two out of five children in Africa below the age of 15 work and are not in school, enrollment rates have fallen and that it is believed that the 40 million children already not in school will rise to 60 million by the year 2015. Additional problems affecting African youth include disease and abusive child labor practices. Due to extreme poverty, there is a virtual slave trade in child workers and concubines in such places as Togo, Benin, and Nigeria.

The actual educational system in many African nations has been plagued by numerous internal factors. Lack of jobs and general disillusionment with the bureaucracy, have led to an exodus of many of the continents top scholars, professors, and entrepreneurs. Widespread student and teacher strikes have, in some cases, shut down major universities for months at a time. The educational structure itself has often been inherited directly from European colonizers, and many have charged that it remains prejudiced against African culture and is otherwise not suited for the needs of Africans.

Speaking at the opening of the Johannesburg conference, Mbeki said, “The incorporation of the African people through colonial education into the capitalist world was deliberately incomplete, designed to create economic dependents, an exploited class of laborers, rather than entrepreneurs and economic producers.” In the speech, distributed by the African National Congress Newswire on December 6, Mbeki added that the post-colonial era has not significantly changed the balance of power, with a native elite, often subservient to the former colonial powers, now controlling the persistently exploited masses.

While Mbeki’s analysis of the nature of African education is certainly insightful, it seems he is still basing his model of renewal on Western capitalist society. Mbeki’s educational vision is predicated on “an understanding of the needs to expand our economies through entrepreneurship, through creating conditions favorable for job creation.” As education must inevitably serve the interests of society at large, it becomes important to scrutinize what those interests might be. Like any American or Western leader, Mbeki seems most interested in making his country, and in this case, the African continent as well, successful in today’s global market. While he questions the colonial notion that education is only for the purpose of creating subservient laborers, Mbeki seems prepared to sell the fate of the African masses as long as their labor lends itself to African development.

A close look at the life of an average American laborer, and the educational system that produced him/her, reveals that the Western example of product orientated education and labor is perhaps not so exemplary. American families are often required to lend both husband and wife to the labor force, where both parents may work in excess of 40 hours per week. Families might have money for multiple cars and large televisions, but many observers say the effects of the lack of time spent with children has disastrous effects. Public school teachers say children are unmotivated to learn and that most of their time as teachers is taken up with things that should have been taught by parents. The culture of violence, drug abuse and sexual indulgence that predominates in much of the school system is well documented. America and other Western nations might be the most developed in the world, but their children are increasingly neglected and it is already a matter of time before the problem catches up with them. Already, America spends more money on prisons than schools.

Mbeki is correct in recognizing that the future of the African continent lies with the educational system. But rather than adopting wholesale the Western example, African nations must do more to protect native cultural values. Mbeki himself recognizes that the “African child” has in the past been divorced “from his or her own experiences and environment, through systematic processes of alienation and also assimilation.”

Mbeki and other African leaders should be wary, given Africa’s recent past, of once again trying to assimilate into the Western culture, even if this time it is under the guise of globalization and free markets. A participant of the Johannesburg conference, the National Education Statistics Information Systems (NESIS) for Africa, has itself recognized that “assessment models” of African education ignore “the tremendous knowledge gained through non-formal, and informal education — including African indigenous education.” African reformers should perhaps look for ways of incorporating elements of indigenous educational systems into the structure of the inherited colonial education system, rather than simply updating one Western model for another.

———

Zakariya Wright is a regular contributor to iviews.com

Arabic

Arabic English

English Spanish

Spanish Russian

Russian Romanian

Romanian korean

korean Japanese

Japanese